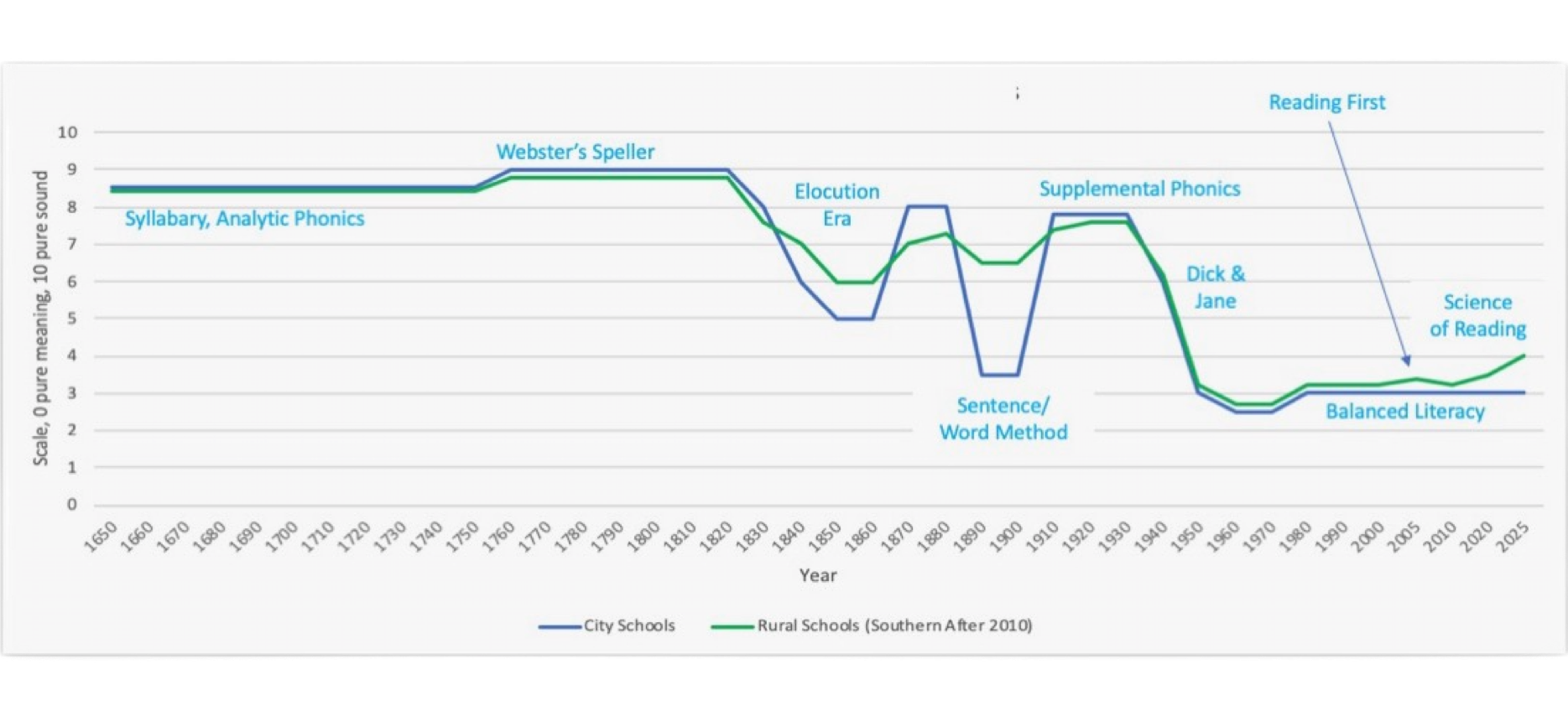

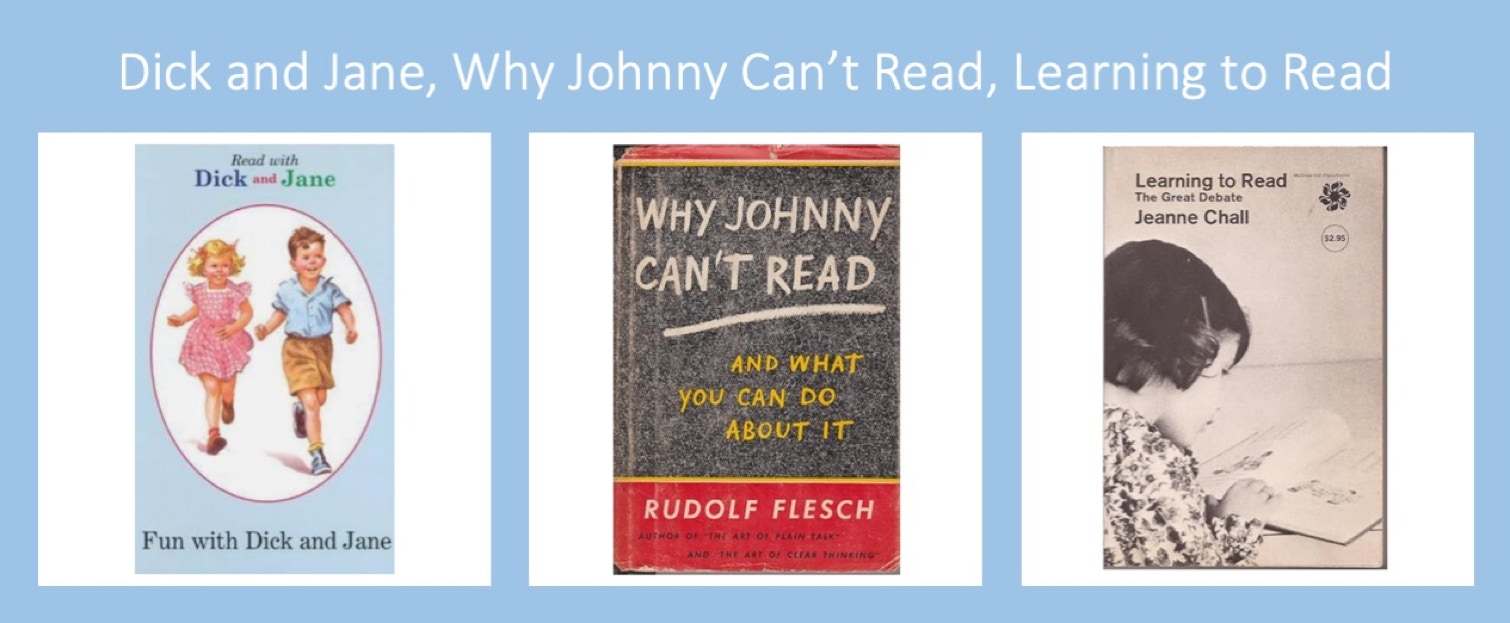

"Teaching the reading of alphabetic print by its "sound" is the correct way.

Teaching the reading of alphabetic print by its “meaning" is the incorrect way.

Obviously, if “sound” and “meaning” methods for the teaching of alphabetic print are mixed, then the mixture is incorrect in direct proportion to the emphasis given to the “meaning” method."